By: David A Fein, MD

Medical Director

Princeton Longevity Center

Two patients return to your office for follow-up. The first is a 45 year old male. Two years ago his LDL cholesterol was 130 and his coronary calcium score was 80. Today his LDL is down to 75 on Crestor 10 mg per day but his coronary calcium score has increased to 112. You tell him to increase his Crestor to 40 mg. The next patient is a 55 year old male who you saw last year when his coronary calcium score was 320. You started him on a statin and low-dose aspirin. Today his LDL cholesterol is 68 and his coronary calcium score is 355. You tell him congratulations we have stopped your plaque from progressing, continue your current treatment and we have brought your cardiac risk way down.

Was your treatment decision right for both patients? One of them? Neither?

The short answer: there is no way to know from that data.

In untreated individuals with non-zero calcium scores the average rate of increase is about 40% per year. That means that generally coronary calcium scores will double about every 2 years. Several published studies have shown that about 95% of the myocardial infarctions that occur will be those patients who have had greater than a 15% per year increase in coronary calcium scores. That’s great for treating populations. But is your patient who had only a 10% increase in his score going to be in the 95% who are safe or is he going to be one of the 5% who infarct anyway? And can you truly tell the patient with the stable score he can relax? Three problems stand in your way.

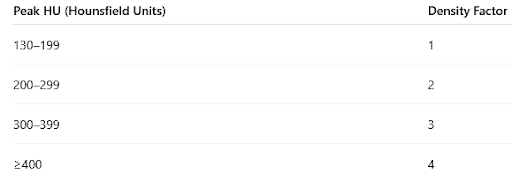

Problem #1 is that you need to understand how the Agaston Calcium Score is calculated. The calcium score you see reported is determined by multiplying the volume of plaque present at each spot in a coronary artery times a density factor which is determined based on the peak attenuation (based on Hounsfield units of each voxel) of that plaque. The denser the calcification in that plaque, the higher the density factor.

So coronary calcium scores can increase because the total volume of calcified plaque has increased. And the score can also increase simply because one small spot in that plaque has become more densely calcified. Even if your patient has not made any new calcified plaque but a spot within one of the plaque went from 198 HU to 205 HU (an insignificant change and likely within the range of inter-scan variability) the calcium score for that plaque will have doubled.

For patient whose score went from 80 to 112, it is possible he has made new calcified plaque but it is also possible that there was just a slight increase in calcium density somewhere in one or more of the spots of plaque previously present. In that case, it may be more helpful to look at plaque volume. Most software packages for measuring calcium scores can separately report the total Plaque Volume or even the Plaque Volume per artery or lesion. If the plaque volume has not increased as much as the overall calcium score, it may be a density issue rather than plaque progression. When comparing serial scans, following plaque volume may be more useful.

The second problem is that coronary calcium scores may increase on average 40% per year in untreated individuals but it is very likely that it is a stepwise increase rather than a continuous increase. Plaque starts off as non-calcified plaque and this is not measured in a coronary calcium scan. There is still some debate as to how and why plaque calcifies. Calcification is a generic response to chronic inflammation may also be occurring as a result of plaque necrosis and plaque rupture. If sub-clinical plaque rupture is the main mechanism for converting non-calcified plaque to calcified plaque then it makes sense that there could be quiescent periods during which there is little change in the calcium score followed by a sudden increase in calcification present. So it may seem reassuring that the patient whose score has increased by only about 10% from 320 to 355 is in a safe zone with a good therapeutic response. But it is also very possible (maybe even likely) that given more time you will see his score suddenly increase and the average rate of increase over a longer timespan may indicate that plaque rupture is still occurring and more aggressive therapy is warranted.

Problem #3 may be the biggest problem of all. There is a general consensus that calcified plaque is “more stable” plaque less prone to plaque rupture. This could be because the calcification actually makes rupture less likely but it could also be that the plaque became calcified after already having had sub-clinical rupture and no longer has the same morphology that predisposes to further rupture. Either way, it is the non-calcified plaque that appears to present the higher risk of plaque rupture and myocardial infarction. Since the coronary calcium score cannot include non-calcified plaque, there is really no way to know whether the patient with the stable score is still aggressively making new vulnerable plaque and there is also no way to know if the patient whose score increased is simply calcifying the plaque that was present before starting therapy but subsequently stopped making any new plaque and is actually a therapeutic success.

For these reasons, while cardiac CT imaging to measure coronary calcification was a paradigm shift in the stratification of risk and treatment decision-making, it is really no longer adequate. Coronary CT Angiography can detect and measure both calcified and non-calcified plaque. While CT Angiography was initially focused on measuring stenosis and ruling out acute obstruction or thrombosis, in recent years the emphasis has shifted to plaque characterization and quantification. We can measure the volume of plaque that is present in each individual segment of each artery and categorize that plaque as calcified, non-calcified and low-density (higher risk) plaque.

Identifying on-going development of new non-calcified plaque indicates that the current treatment has been insufficient to stop further plaque progression. Conversely, the absence of new plaque may be an indicator of treatment success even in the absence of having reached “standard” cholesterol goals. A decrease in non-calcified plaque accompanied by an increase in calcified plaque can be an indicator of treatment success as the previously present non-calcified plaque evolves without new plaque forming.

A role remains for coronary calcium scores in the initial assessment of a patient’s cardiac risk to help in guiding decisions as to when to start pharmacologic therapy. To assess the efficacy of that therapy requires obtaining a Cardiac CT Angiography as a baseline prior to starting therapy and then reassessing plaque character and volume periodically to titrate the intensity of therapy.